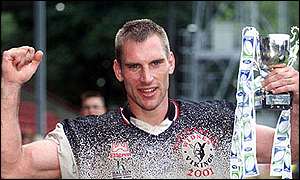

Phil Cantillon during his Widnes Vikings days

ARUGABLY, the transition in the role of the hooker began with Benny Elias.

Given that the Lebanon-born, former Australia international transitioned from half-back to the number nine shirt when he was first graded by Balmain Tigers in 1981, it should have been no surprise he should bring the slick ball-handling, running ability and creativity to the role.

Of course, back in the early 1980s the front row was still home to some of rugby league’s biggest and meanest bruisers. Indeed, Elias himself was not averse to bestowing physical violence on an opponent when needed – just ask fellow hooker Steve Walters, who famously clashed with him in State of Origin.

But while Elias might have been the blueprint for the role all hookers would be expected to fill in the future, there were two other changes in the game which paved the way for the change what was expected of players in that position.

The first was the decline of the contested scrum, which is virtually unseen in the modern game and removed the need for the hooker to engage in the dark arts of winning the ball at the set piece.

The second was moving back the defensive line at the play-the-ball from five metres to eight and then the 10 metres it is today in 1993, which gave the dummy-half license to run into more open space one he had received the ball.

It did not take long for teams and players to exploit this rule in favour of the attacking team, and an interview with Oldham hooker Richard Russell – who originally went to the club as a loose forward – in 1994 revealed how the changes were affecting him.

“I used to travel with Nicky Kiss (at Wigan) and he had loads of stories about what went on with hookers,” Russell told The Independent’s Dave Hadfield. “I remember thinking, ‘thank God I won’t have to play there.’

“It’s all about getting the best and quickest pass away, although, especially with the 10-metre rule at the play-the- ball, I can have a dart with the ball whenever I see a gap.”

One player who thrived during the early days of the changing demands of a hooker more than any other was Phil Cantillon, whose deft turn of pace and try-scoring ability, combined with the defensive attributes required of the role, showcased everything which would be expected from the modern day number nine.

It was Keighley during the ‘Cougarmania’ era where former Wigan youth team player Cantillon first made his mark, scoring 21 tries in 75 appearances as the club took the second tier of the domestic game by storm.

A short-lived move to Super League outfit Leeds Rhinos followed in 1997, but it was his next stop at Widnes where Cantillon really made his mark on the game.

Even now, 12 years after his final game for the Vikings, Cantillon is revered as a cult hero by the club’s fans thanks to his try-scoring exploits and all-action displays during five years at what is now known as the Select Security Stadium.

A tally of 117 tries from 152 appearances between 1999 and 2004 tells its own story, but it was under coach Neil Kelly where Cantillon truly thrived, breaking famed Wigan and Great Britain star Ellery Hanley’s world record with 48 tries in a season as Widnes stormed to the 2001 Northern Ford Premiership title – seven of those alone coming in one game against Rochdale Hornets.

The Vikings’ elevation to Super League gave Cantillon the chance to showcase his talents at the highest level. Yet a new generation of dynamic, modern hookers were already making their mark, with the likes of Keiron Cunningham at St Helens, Rob Burrow at Leeds and Jon Clarke at Warrington Wolves all blazing a trail for attacking number nines.

Great Britain honours therefore eluded Cantillon, although he was capped by both England and Ireland, along with playing in the 1996 Super League World Nines for England.

Cantillon eventually brought his career to a close in 2007 after a spell with Rochdale and a player-coach role with the now-defunct Blackpool Panthers, but his legacy in defining what the role of hooker was to become will not be forgotten by anyone who saw him play.

As for how the role will develop, who better to ask than the aforementioned Elias?

“I believe the bloke that dominates the game is the number nine because he touches the ball the most,” Elias told Australia’s Daily Telegraph last year.

“It is not by accident that the Melbourne Storm have been up there (as the NRL benchmark) for the last decade and Cameron Smith has led the way for them.

“But now we are in a new era I think where footwork and speed will be essential for a number nine.”

The Super League stats from last season seem to back that up. St Helens’ James Roby led the way with 306 runs from dummy-half, while Paul Aiton, Luke Robinson and Danny Houghton all having over 200.

But their defensive role should not be forgotten as well. Roby and Houghton led the way for most tackles made in Super League in 2015 by some distance, with 1,041 and 1,359 respectively.

In whatever way rugby league gameplay evolves, it seems as if the ever-changing role of the hooker could have a key part in it.

I vividly remember Phil Cantillon at Keighley. I was always amazed Wigan of all clubs let him go, and it was a great, great call of Phil Larder’s to sign him, but perhaps he’d have made a bigger career if he’d held out for a Superleague side. I remember him outsprinting everyone else *up the slope* at Batley to score from 50 yards plus out of the acting half position, running at the offside defender and the ref. He did much the same to Salford at Old Trafford in a Premiership final but they shamelessly tripped him and got away with it.

LikeLike

A great player Catillon was, so quick and elusive you needed a sledgehammer to knock him down

LikeLike

Awesome player who I loved to watch and he always had his sleeves up and socks down

LikeLike